European regulations have changed little despite what has been expected since 2001 when an EU Clinical Trials Directive was introduced with the aim of harmonising regulations across Europe. Despite its original purpose, the directive - adopted throughout Europe by 2004 - along with overinterpretation of its requirements, led to a dramatic increase in clinical trial bureaucracy which is now impeding investigators and stifling cancer research.

“We fully respect the laws governing clinical trial procedures but, over the last five to 10 years, over-interpretation and misinterpretation of these regulations has become widespread,” explains Dr José Luis Pérez-Gracia, University Clinic of Navarra and Health Research Institute of Navarra (IdiSNA), Pamplona, Spain, Chair of the newly established ESMO Clinical Research Observatory (ECRO) Task Force.

The ECRO Task Force aims to address the causes of the bureaucratic burden and, in collaboration with researchers, industry, regulators and other stakeholders, works to streamline procedures and improve efficiency for the benefit of patients. The initiative was fuelled by the findings of an ESMO online survey of clinical investigators which underlined the bureaucracy facing today’s researchers and suggested that administrative procedures could be reduced without compromising patient safety or data quality (ESMO Open 2020;5:e000662).

“The increase in bureaucracy makes poor use of the time of busy clinicians, is frustrating and demotivating, and makes young physicians reluctant to become involved in research,” adds Pérez-Gracia.

“The increase in bureaucracy makes poor use of the time of busy clinicians, is frustrating and demotivating, and makes young physicians reluctant to become involved in research”

“The good, the bad and the ugly”

Following implementation of the EU Directive, the number of European trials submitted for grants or ethical review was estimated to have fallen by 30-50% and the proportion of non-commercial trials reduced from 40% to 14% (PLoS Med. 2009 Nov;3(11):e1000131).

Clinical trial standards are defined by the long-established Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines and additional local regulations. Experienced investigators currently believe that Clinical Research Organisations (CROs) which coordinate clinical trials on behalf of pharmaceutical sponsors frequently make administrative procedures longer and more complex than they need to be. They are also critical of cumbersome online platforms and exhaustive and often inappropriate training courses. There are concerns that these trends are now finding their way into academic research too.

Dr Benedict Westphalen, Comprehensive Cancer Centre, University of Munich, Germany, highlighted pharmacovigilance procedures as one of the most time-consuming aspects of clinical trial bureaucracy. As principal or deputy principal investigator of 15-20 of the 50 early and late-phase clinical trials typically running at his institution, he receives a mountain of documentation.

“I can receive 50 automated emails per day for each trial, in which I may only have one or two patients, and there is currently no good way to sift out what is important. This is surely not the way we should be assessing something as critical as safety in our clinical trials. We need tier-systems for this type of information so that we can prioritise looking at relevant data for our daily practice,” he says.

“This is surely not the way we should be assessing something as critical as safety in our clinical trials. We need tier-systems to prioritise looking at relevant data for our daily practice”

Predictable findings from the ESMO survey

The results of the ESMO online survey, which involved nearly 1,000 ESMO members, faculty and experienced clinical researchers and investigators attending the ESMO 2019 Congress in Barcelona, show there was good agreement that administrative procedures in clinical research are excessive (mean score 8.3 on a scale of 0-10) and an obstacle to development of clinical research (mean score 8.2). There was also consensus on the feasibility of limiting such procedures without compromising the safety and rights of patients and the quality of data (mean score 8.1), and on the need to incorporate physician feedback on procedures related to clinical research (mean score 8.6). Scores were highest among oncologists with more than five years of experience in clinical research.

“These findings were not unexpected and they reflect the opinions of a large number of experienced and highly respected investigators,” comments Pérez-Gracia. “If we had done this survey seven to 10 years ago, I doubt we would have got scores of more than six.”

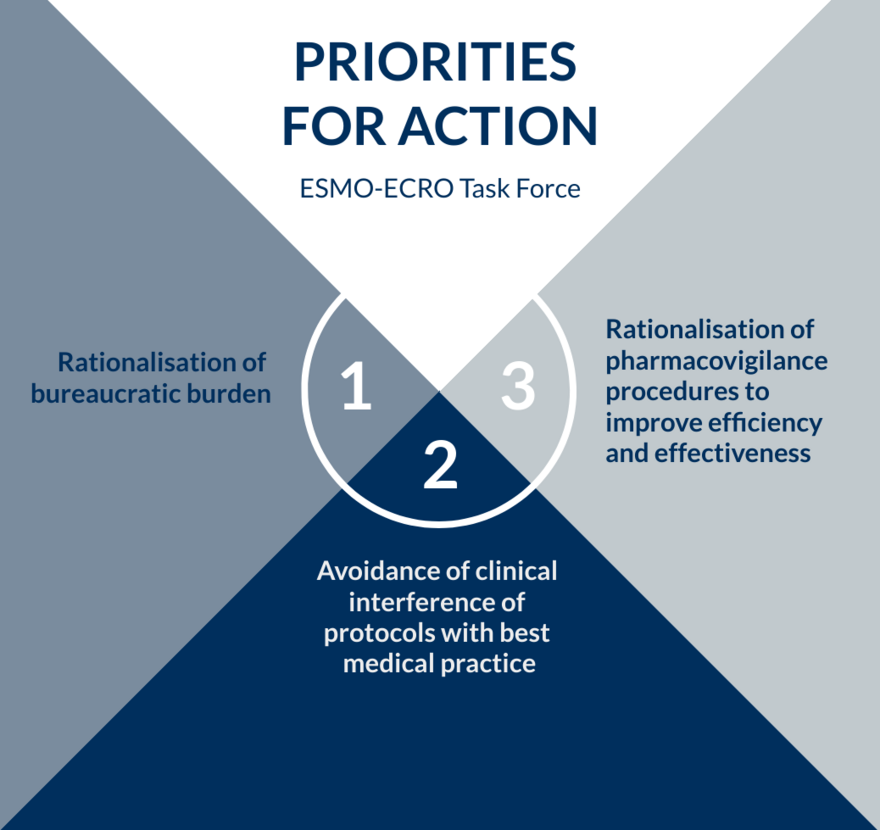

Priorities for change

Initial areas for action have been identified by the ECRO Task Force focused on rationalising documentation and procedures and avoiding interference with best medical practice by protocol requirements (see Box below).

“The patient must always be the first priority in clinical research and we cannot have occasions where the protocol interferes with treatment that is in the best interest of the patient. Fortunately, this doesn’t happen very often but when it does occur, we need to have flexibility in the protocol,” says Pérez-Gracia.

The ECRO Task Force intends to engage all stakeholders in discussions about how priority areas can be addressed and to obtain balanced feedback from investigators through further surveys and research to characterise common problems. It also wants to foster the involvement of experienced clinical investigators in the training of study monitors to provide the clinical perspective of research practicalities.

Westphalen strongly supports ECRO’s priorities for rationalising documentation, including optimising delegation of trial procedures from investigators to other members of research teams.

“I often have to take responsibility that every measurement for every patient is correct. But it would make much more sense if the team members who collected all these data, and are clearly much closer to the information, are able to sign off on their accuracy,” he explains.

Like Pérez-Gracia, Westphalen would like to see more flexibility in protocols and more understanding from clinical trial organisers and monitors about administrative issues.

“It’s difficult to negotiate changes in protocols at any stage and, of course, we need fees generated from clinical trials to pay our research teams. In addition, running clinical trials is part of our mission to bring the most innovative treatments to patients. Once you’re on the ‘hamster wheel’ it’s very difficult to get off,” he says.

Westphalen would also like to see a reduction in the bureaucracy of contracts at all levels and stages of the process. He explains that contracts and budgets frequently have to be negotiated not only between institutions but with individual departments such as radiology, laboratories and pharmacy. Sponsor deadlines are an added pressure and if these are not met, institutions risk not being invited to participate in future clinical trials.

“Contracts are a major show-stopper from an administration perspective. Even when you have worked with a sponsor many times before, you have to start at the beginning again and a fixed template flies into legal and compliance and then gets pushed around as if it is the first time you have ever spoken to each other,” he says.

Moving forward

Preliminary responses to the ECRO initiative have been positive, with both researchers and pharmaceutical sponsors recognising that the problem of bureaucracy in clinical research does need to be addressed.

“We plan to hold consensus panels to listen to all those involved in clinical research, including CROs, regulators and patients. Through ESMO, we can expand and coordinate our activities with oncologists and other specialties and really make a difference,” says Pérez-Gracia.

The Task Force plans to collaborate with other national and international associations related to clinical research, especially in oncology, in order to endorse, revise and improve the initiative. As progress is made, it will publicly acknowledge all stakeholders who succeed in reviewing and simplifying procedures without compromising – but hopefully improving – the quality of clinical research, and consequently, the well-being of patients.

Westphalen applauds ESMO for taking on such a large and important topic that no individual research group can tackle alone.

“The beauty of an independent society becoming our spokesperson is that it can bring together all the different sectors involved in clinical research, including pharmaceutical partners and regulatory agencies,” he says. “We need to create a clinical trial environment that puts our patients first and delivers the best outcomes in terms of data but without the bureaucratic burden that we have today.”