An ESMO study shows that precision oncology is out of reach for the majority of patients, with costs of technologies and reimbursement policies acting as major barriers

Cancer patients’ access to genetic testing is not keeping up with the pace of discovery of targetable mutations and the development of personalised therapies, with a risk of seeing precision medicine deepen health disparities across and within countries. That is the sobering reality revealed by the ESMO Study on the Availability and Accessibility of Biomolecular Technologies in Oncology in Europe, published today in Annals of Oncology.

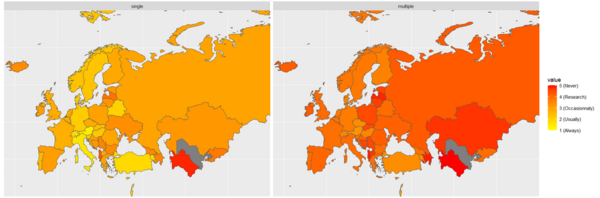

With data received between July and December 2021 from 201 field reporters in 48 countries and amended through an open peer-review process, the study mapped the availability, prices and out-of-pocket costs for cancer patients of different biomolecular technologies, from basic single-gene techniques all the way to complete genomic profiling.

The results show that while immunohistochemistry and basic single-gene techniques like fluorescence and chromogenic in situ hybridisation, PCR and microsatellite instability were widely available in routine clinical practice, patients’ access to more advanced technologies including next-generation sequencing (NGS) panels was highly heterogeneous both across Europe and within individual countries. Small (<50 genes) or large (>50 genes) NGS panels and Tumour Mutational Burden were only occasionally available in routine practice in some high-income EU countries and limited to clinical trials or research in the majority of low and middle-income countries (LMICs). Meanwhile, the most comprehensive technologies such as whole exome sequencing, whole genome sequencing, RNA sequencing, genomic assays and liquid biopsies were available only in clinical trials or research in high-income countries, and never in LMICs.

According to lead author Dr. Arnaud Bayle, Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus, France, these results are a wake-up call that the large NGS panels which are the gateway to accessing innovative targeted therapies remain largely unavailable in routine clinical practice, keeping precision oncology out of reach for the majority of patients. “Even in high-income EU countries, and even when some innovative targeted medicines are available and reimbursed by statutory health insurance, these techniques continue to be mostly reserved to research and clinical trials, mainly within the large reference centres for cancer,” says Bayle, lamenting a potential inequity in access to treatment for patients.

Tying access to evidence: the example of Italy

With a growing number of genomic sequencing techniques on the market at varying prices, oncologists feel the need for more structured guidance and efficient strategies to be able to offer the right tests, to the right patients, at the right time. In the study, testing practices for specific biomarkers were also assessed. Using the clinical evidence criteria of the ESMO Scale for Clinical Actionability of molecular Targets (ESCAT) to categorise molecular targets, investigators found that even certain alterations classed as ESCAT tier I, for which existing therapies are deemed ready for use in routine practice, were inconsistently tested for across four 'big killers’ — lung, prostate, colon and breast cancer. Disparities in access were particularly pronounced for some of the more recently validated biomarkers or those requiring complex sequencing techniques, such as NTRK and RET in lung cancer, both across and within countries.

Multiple applications for the ESCAT

The ESMO recommendations on the use of NGS for patients with metastatic cancer published in 2020 represented the first academic attempt to prioritise patient groups for advanced testing in tumour types where multiple ESCAT tier I and tier II alterations are known, which single-gene techniques would be ill-suited or unable to identify (Ann Oncol. 2020 Nov;31(11):1491-1505). Since 2021, all new or updated ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines also incorporate the authors’ assessment of relevant molecular targets according to ESCAT terminology.

In spite of the fact that genomic alteration scales like the ESCAT can play an important role in informing clinical decision-making, study results revealed that these tools were routinely used by oncologists in less than one third (27%) of countries.

Dr. Joaquin Mateo, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology, Spain, Chair of the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group which developed the ESCAT scale, sees reflected in the findings a dual challenge of precision oncology. “Focusing only on making NGS testing available without harmonising the way we interpret the genomic data is still going to result in inequalities, so the two aspects should be addressed in parallel, both at national and international levels,” he observes. “The ESCAT scale can help here because it provides a common terminology to define and rank levels of evidence for matching a drug with a biomarker, and it can be truly used throughout the world. Contrary to other available scales, in fact, its main stratification criterion is the quality of the clinical trials that support different alteration-drug matches independently of the drugs’ FDA approval status.”

Although the tool was initially developed with the objective of making genomic reports and clinical trial results easier to interpret and act on for oncologists, a novel application for the ESCAT scale was recently adopted in Italy, where the Ministry of Health in February officially launched a fund for the statutory reimbursement of NGS testing for biomarkers based on the ESCAT stratification of clinical evidence. All tests for tier I and tier II molecular alterations will now be covered by the country’s national health service, a move that comes in the context of the implementation of a national five-year programme to make all genomic tests that have therapeutic or prognostic implications reimbursable for patients.

“This decision does not mean universal access to NGS, but it is certainly an extension of financial coverage for all those tests which give patients access to drugs that impact their outcomes, representing a first step towards the democratisation of precision medicine,” says Prof. Giuseppe Curigliano, Chair of the ESMO Guidelines Committee, who also views the fund as an incentive for a more widespread use of this technology. “The large-scale use of genomic testing poses challenges related to costs, deciding which techniques to reimburse for which patients and the need to educate more doctors and genetic counsellors on cancer genomics. Nonetheless, the need for testing and the services associated with it will only continue to increase in the future,” he adds.

According to the ESMO study, the lack of reimbursement of more advanced NGS techniques, reported by more than half (59%) of participants compared to just one in four (24%) for single-gene tests, is one of the most common barriers to access testing and leads to significant out-of-pocket expenses in the countries surveyed.

For ESMO President Andrés Cervantes, these findings confirm a widespread need for targeted policies to address the gaps in infrastructure and funding for personalised treatment in oncology. “The study also found that initiatives for the implementation of innovative molecular technologies, which are key to accelerating the transition of novel diagnostics into routine practice, had been implemented in only one out three countries in Europe,” he highlights. “The example set by Italy in this respect is one for other countries to follow, and ESMO welcomes the Italian government’s decision to make ESCAT evidence tiers legally binding for access to testing. It is a recognition of our Society’s ongoing efforts to build a framework for precision medicine that reaches all patients who can benefit from it.”