Increased use of molecular profiling is progressively improving decision-making processes in oncology compared with 20 years ago and helping to shape tomorrow’s clinical trials in targeted therapies

The advent of targeted therapies has brought numerous benefits to patients, but what can be learnt about the design of trials that have been conducted in precision oncology so far to help guide future improvements?

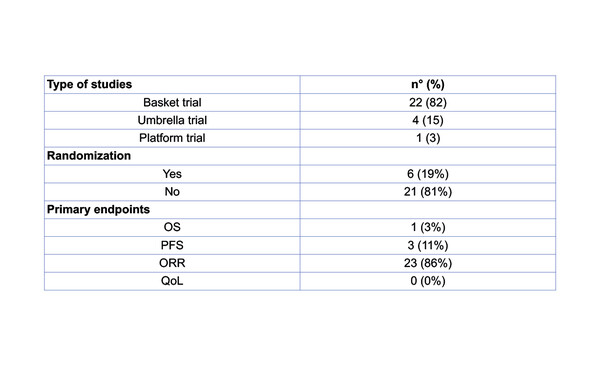

Presented at the Molecular Analysis for Precision Oncology Virtual Congress 2021, a systematic review of all the precision oncology trials published in the last 20 years reports that more effort needs to be made to better design clinical trials and achieve more solid evidence in the field (Abstract 8P). Researchers identified twenty-seven trials (Table), which were mostly basket trials (82%) and were non-randomised (81%). Overall response rate (ORR) was the primary endpoint in 86% of trials and progression-free survival (PFS) data were reported in the vast majority of publications (91%), with progressive disease being the most common outcome (89%). However, the proportion of patients who were actually enrolled was low – on average, 114 patients per trial – and ORR was recorded in only 11% of patients. Only 52% of the studies reported overall survival (OS) data. Also, toxicity data were included in three-quarters of publications, while none of the publications contained patient-reported quality of life data.

In spite of these findings, there has been some improvement. Dr Elena Garralda from Vall d'Hebron Institute of Oncology, Barcelona, Spain thinks that the more recent evolution of clinical trials may not be captured in the review and that the included trials may have been heterogeneous in their methodology. “Trials have evolved considerably over the last few years. Incorporation of biomarkers to aid patient selection at early stages, for example in phase I trials, is shortening drug development time. Another important advance is the use of new clinical trial designs, such as adaptive platform trials, which enable decisions to be made on the information as it is collected, improving the efficiency of the process and reducing the number of patients involved before approval,” she says, noting that the ‘change in oncology mindset’, with increased use of molecular profiling, is helping to enhance clinical trial recruitment.

“Also, we now have the ESMO Scale for Clinical Actionability of molecular Targets (ESCAT) to rank molecular targets based on available evidence and this is helping to more accurately define what ‘guided treatments’ truly are – this was not so clear 10 to 20 years ago.”

As proposed in another e-Poster and recent publication (Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:e446–e455), a new concept in clinical trial design – the late phase I trial – aims to circumvent treatment failure due to suboptimal drug concentrations and improve efficacy (Abstract 9P). It is thought that some patients who are chronically exposed to targeted therapies experience tachyphylaxis. Furthermore, the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) is not always reached in phase I studies. The primary goal of the late phase I trial presented at MAP 2021 Virtual is to define an alternative MTD of an agent in patients who were chronically exposed (MTDc) and had an initial benefit from targeted therapy, but who subsequently progressed without an identified resistance alteration. Intrapatient dose escalation may increase drug concentrations and restore drug activity.

Garralda thinks this concept is worth exploring and agrees that late escalation of targeted therapy may be the solution to reverse resistance in some patients; however, she thinks a challenge will be determining which patients may benefit, without exposing them to unnecessary toxicity. “Other strategies to ensure we are testing the correct dose include greater use of pharmacokinetic guidance and bigger phase I trials incorporating randomisation strategies,” she concludes. “As another step forward, we need to address how to incorporate liquid biopsies and genomic results in a more dynamic way. We also need to consider how to design platform trials to test combinations based on the genomic profile of each patient – these are further innovations required in the future.”

Abstracts presented:

Filetti M et al. Clinical trial design in the era of precision oncology: An overview of the last 20 years. MAP 2021 Virtual, Abstract 8P

Benitez JC et al. Late phase I studies: Concepts and outcomes of a new clinical trial design. MAP 2021 Virtual, Abstract 9P