Tumour-only molecular profiling can spot hereditary cancer syndromes but resources are critical to make the most of this piece of information

Pathogenic germline variants are a common finding in cancer patients referred for complex molecular profiling but there is still no standardised approach to manage this ‘incidental’ piece of information, as suggested in a poster presentation at the Molecular Analysis for Precision Oncology Virtual Congress 2021 (MAP 2021 Virtual) (Abstract 13P).

“If we are to use the information from next generation sequencing (NGS) effectively for the benefit of patients, we need to raise awareness among oncologists about the possible germline origin of pathogenic variants and provide them with the training and support they need to understand the implications of these variants for patients and their families,” says Dr Judith Balmaña from Vall dʹHebron Institute of Oncology, Barcelona, Spain, putting the analysis presented into the current clinical scenario.

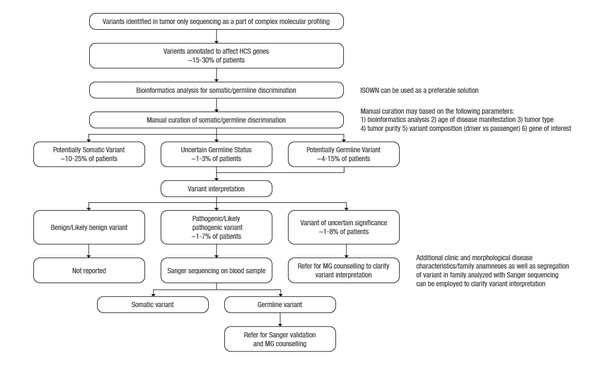

Within the last 10 years, the use of extensive tumour sequencing panels to direct cancer treatments have largely replaced hotspot mutation genotyping. These types of panels also screen for cancer-susceptibility genes, a subset of which can be pathogenic in the germline setting. However, the handling of these findings can be challenging for oncologists, particularly with tumour-only analyses, which are currently the most common approach used in the clinic.

The analysis, conducted by a collaboration of researchers, including the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, reported that among 183 patients with colorectal (19%), pancreatic (13%), lung (10%) and other tumours, 17 of 56 sequencing variants found in genes associated with hereditary cancer syndromes (HCS) were of germline origin. Six of these variants were pathogenic (PV) or likely pathogenic (LPV) and 9 were variants of uncertain significance (VUS). Bioinformatics prediction of variant origin was concordant with manual curation for the 97% missense variants in HCS-associated genes. The authors estimated that Sanger sequencing of normal tissue would be required for 1–7% of cases (PV or LV in HCS genes) and genetic counselling in 2–15% of cases (PV, LV or VUS in HCS genes).

“The recommendations from the ESMO Translational Research and Precision Medicine Working Group provide a useful algorithm for dealing with the identification of variants of germline origin in tumour testing (Ann Oncol 2019;30:1221–31). However, we have to put the infrastructures and resources in place to enable us to act on these findings,” she says, agreeing that the identification of germline mutation is only the tip of the iceberg.

Balmaña highlights a number of challenges, mainly centred on ensuring the expertise and availability of experienced oncology team members in interpreting results that are sometimes reported as ‘incidental’ findings. “Firstly, patients need to be well informed by their doctor about the full implications of tumour testing and why it is being conducted before they provide consent,” she advises. “The team also has to be able to provide patients with easy-to-understand information on the results of testing and the impact of findings beyond a therapeutic targeted approach, including, where necessary, genetic counselling. Managing these ‘incidental’ findings effectively can improve patient outcomes if this is done properly – and this should be the aim for all oncologists,” concludes Balmaña.

Abstract presented:

Ivanov M et al. Incidental germline findings from tumor molecular profiling for precision oncology: Is it common and how to manage? MAP 2021 Virtual, Abstract 13P

On-demand ePoster Display