26 July 2021 saw the US FDA approval of the first immunotherapy agent – pembrolizumab – for use in combination with chemotherapy for the neoadjuvant treatment of high-risk, early-stage triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Does this herald the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) as the standard neoadjuvant therapy for high-risk TNBC? Or do the risks outweigh the benefits?

These key questions will be the focus of the Controversy session ‘Are we ready to consider chemotherapy + checkpoint inhibitor as the preferred option in the neoadjuvant setting?’ taking place on 21 September 2021, 14:20 – 14:55, Channel 6 at the ESMO Virtual Congress 2021.

Not since the introduction of trastuzumab – a drug that radically changed the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer – and recently with olaparib in germline BRCA1/2-mutated disease, have we seen such a marked improvement in clinical benefit as that observed with neoadjuvant ICI therapy in TNBC. This disease remains a major unmet need and ICIs provide a dramatic transformative opportunity for patients with these types of tumours.

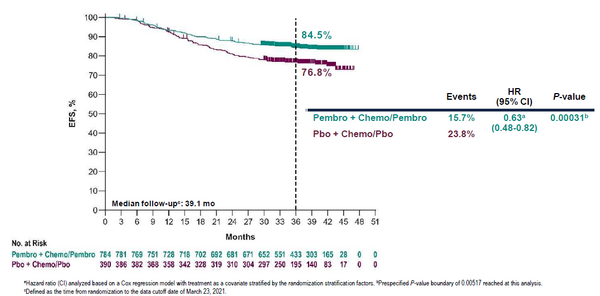

The US FDA decision was based on the KEYNOTE-522 trial, which demonstrated that adding pembrolizumab to chemotherapy led to a marked and significant 37% reduction in the risk of an event-free survival event (hazard ratio 0.63; p=0.0003, Figure). In addition, the risk of distant recurrence decreased by 39%, leading to a positive trend of overall survival improvement (hazard ratio 0.72; p=0.0321, results still immature). The findings are supported by earlier data from the GeparNuevo trial showing the survival benefits of adding durvalumab to neoadjuvant chemotherapy for TNBC.

Investigating the potential for ICI use in the neoadjuvant setting really took off following clinical confirmation of their benefit in metastatic TNBC. We now have two independent trials – KEYNOTE-355 and IMpassion130 – showing a clinical survival improvement with the addition of ICIs to first-line chemotherapy in metastatic disease, which have supported regulatory approval in this setting. And the clinical findings were built on a sound biological rationale. TNBCs typically show high engagement of the immune system with infiltration of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). However, immune reactions lessen in intensity as the cancer progresses so it would appear logical to utilise ICIs in early disease, when the immune system is more reactive and less susceptible to the tumour’s immune escape mechanisms. Trials with ICIs in TNBC in the adjuvant setting are ongoing and while we await the results, it is worth noting that several preclinical and clinical studies suggest a higher efficacy of ICIs when given in the neoadjuvant, rather than the adjuvant, setting.

When monitored and managed effectively, toxicity should not generally prevent the use of ICIs. However, there is the possibility of serious and, even if extremely rare, potentially fatal immune-related adverse events with ICIs, and toxicity is something that needs to be considered on an individual patient basis. It is also one of the prime reasons for ensuring that only those patients who are likely to respond well to ICIs receive them.

All in all, deciding which patients should receive ICIs will be a matter of balancing efficacy, toxicity and cost. Without good reasons to deny this curative option, this therapeutic opportunity should be offered to almost all patients with high-risk TNBC and considered the new standard of care. However, we know from the KEYNOTE-522 trial that some patients still have good outcomes on chemotherapy alone, so we urgently need biomarkers to help identify which patients will do better with addition of ICIs and which will do just as well without them. However, at present, we lack such predictive biomarkers. Using TILs to refine prognosis in patients with limited clinical stage, such as cT2N0, may be helpful in defining a subgroup of patients with a risk of recurrence sufficiently low to consider it probably not worth the addition of pembrolizumab.

Finally, many breast oncologists have no or only limited experience in the use of ICIs so there will be the need for education of health professionals before these agents can become established as part of routine neoadjuvant therapy for TNBC.